DIARY: Viollet-le-Duc's Imagination

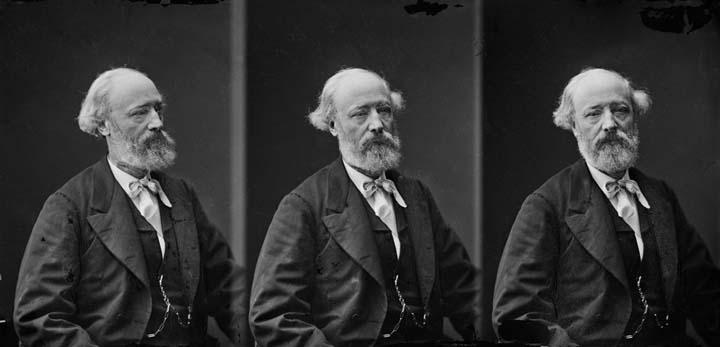

Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (1814–1879) was a visionary French architect who, among other things, devised the structural system that made it possible for Gustav Eiffel’s Statue of Liberty to sport a skin of self-oxidizing copper. His approach to materials was: understand the properties and the form will ensue. Many years later, this idea was popularized by Louis Sullivan, who coined the phrase, “Form Follows Function”—a statement widely considered to be the origins of modern architecture in the Western world.

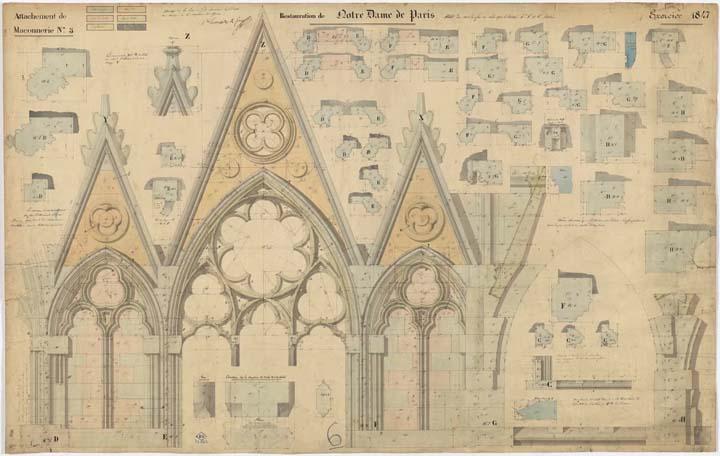

Oddly, this mastermind has been largely overlooked in the US until his plans for the restoration of Notre Dame Cathedral in the 1850s [below] made it possible for France’s Ministry of Culture to execute the restoration of the Gothic masterpiece, following its near-destruction by fire, in 2019,in record time.

Violette-Le-Duc, as he is known, was a true outlier. Born to a well-connected family in the world of French patrimony In the arts, he refused to study at the École des Beaux Artes because drawing from plaster casts of Greek sculptures was anathma to him. Instead, he drew his way through ancient history by traveling to historic sites in Greece and Italy. Below: View of the Antique Theatre at Taormina’ (1840

Upon his return to Paris, he took a job as an apprentice in architecture and quickly established his credentials as a thinker and builder. Around the same time that Paris was shaped into a modern city by Baron Haussman, he executed massive restorations of historic cathedrals, castles and even the walls of the Medieval city of Carcasson in their entirety.

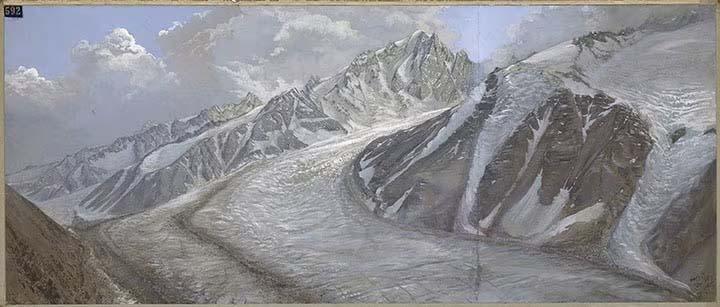

Violette-Le-Duc never made distinctions between the man-made, the geological and archeological. In later years, he spent his summers in the French Alps observing patterns of glaciation, which he transcribed as delicate ink structural drawings and ecstatic watercolors of the great massifs around the Mont Blanc area [above]. These drawings and paintings are currently on view in the extraordinary exhibition, Viollet-le-Duc Drawing Worlds at Bard Graduate Center. The exhibition presents more than 150 of his drawings from all aspects of his work, offerings insigts into his fertile imagination and industrious methods.

Viollet-le-Duc Drawing Worlds is organized by Bard Graduate Center in partnership with the Médiathèque du patrimoine et de la photographie, a department of the French Ministry of Culture. Curated by Barry Bergdoll, Meyer Schapiro Professor of art history in the Department of Art History and Archaeology at Columbia University; and Martin Bressani, William MacDonald Professor at the Peter guo-hua Fu School of Architecture at McGill University; with project coordination by Emma Cormack, BGC Associate Curator. Below: The desk of Violette-Le-Duc. All images courtesy of Bard Graduate Center

A companion publication is available here BGC writes, “Viollet-le-Duc (1814–1879) was nineteenth-century France’s most prominent architect and restorer. This groundbreaking study examines how he used drawing and printmaking as a mode of seeing and thinking and as a means to intensify relationships by capturing the vitality of historical worlds and hidden analogies between human culture and the natural realm.

"Making sense of Viollet-le-Duc’s vast graphic production, scholars consider his imaginative recreations of the most minute aspects of medieval warfare; his approach to the practical tasks of restoring very complex medieval monuments; his experiments in new means of publicly diffusing architectural ideas in the yearly Parisian salons, in didactic manuals, and in children’s books; and even a fantastic project to restitute the original structure of the formidable massif of Mont Blanc. The gamut of techniques employed by Viollet-le-Duc stretches from large painted tableaux to lithographs, steel engravings, woodcuts, gouaches, tracings, and full-scale details. This generously illustrated volume offers an unparalleled window into the architect’s working process and explores how his mastery of the graphic arts helped him harness the power of the press to disseminate architectural knowledge and spread ideologies based on antagonism, most notably nationalism and racism.”

Through May 24 at Bard Graduate Center, xxx West 86th Street, New York, NY Info