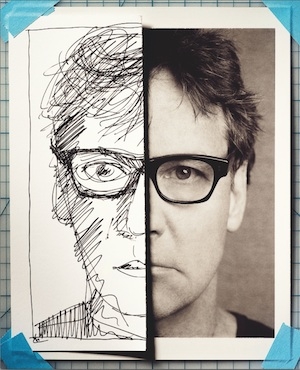

Photographer Profile - Craig Cutler: "You remember imagery with a great idea behind it"

|

|

|

The word itself, which satisfyingly sounds like a pencil scratching on paper, is connected to the word “scheme,” via the Italian “scizzo” (“sketch, drawing”), the Greek “skhema" (“form, shape, appearance”) and various antecedents. A sketch is the manifestation of an idea — fleeting electric impulses in the mind coalescing into a thoughts and a course of action and then given a physical dimension with graphite or ink. The sketch can be plotted carefully or it can happen extemporaneously. It is at once an experiment and an essential form of human communication.

And it is where Craig Cutler begins all his work.

“That’s my thing,” he says. “The sketch is the fun part, if you have something fun to start with.”

Cutler identifies himself as a "conceptual photographer and director" who “turns ideas into images and stories.” He has shot innovative commercial projects for companies like Samsung and NASCAR, editorial work for Esquire, National Geographic, and the New York Times Magazine, and a prodigious number of personal projects ranging from portraits to still lifes and film. He is an interpreter who translates big, unruly or abstract notions into memorable visual moments.

Recently, for instance, he illustrated a story in the Washington Post Magazine on disappearing honeybees by shooting a single bee at work in a honeycomb. “I gave them 11 or 12 sketches for possible shots, but that one told the whole story best.” he says. His image for a Variety cover story about explicit sex on television features a boom mic with furry windscreen poised in front of a nude man’s private parts. A print piece for the New York Cares coat drive showed a shivering Statue of Liberty. In another photo, he evoked the character of Bozo the Clown with a nothing more than well-worn, over-sized blue shoe.

“You need to describe ideas with a simple, strong concept,” he says.

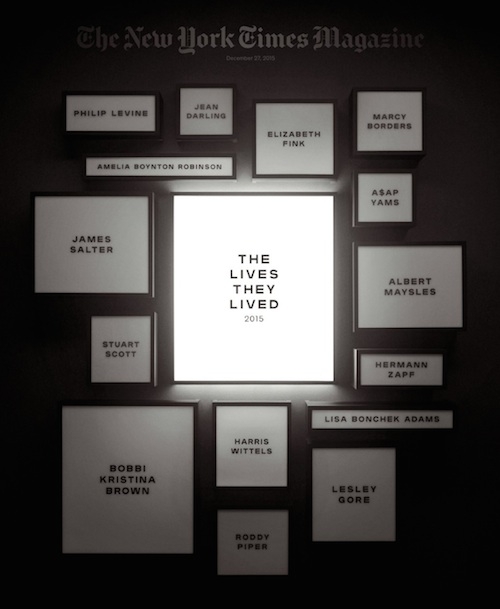

His approach encompasses still and motion work, used interchangeably. A recent cover for the New York Times Magazine's issue about significant deaths in 2015 featured a gallery of picture frames, each illuminated with the name someone who passed, from singer Lesley Gore to documentary director Albert Maysles. In an online animated version, the lighted frames dim to darkness, one after another.

Cutler’s capacity to conceptualize was put to a test — and put on display — with his “CC52” series, a yearlong personal project begun in 2011. Each week for 52 weeks, he designed and executed a new work, some simple and some elaborate. By the end he had created 13 motion projects — including a video of marshmallows roasting slowly and voluptuously — and 39 still pieces that formed a record of his craft.

Where ideas come from is a wonderful human mystery. “When I sketch, I mentally go through the photo shoot in my head. It’s here I decide to move forward or shut it down,” Cutler noted in a 2012 interview. He says that when he starts a project, he has a surge of ideas. “There’s the old saying that your first idea is the best,” he adds.

Idea Exercises

Cutler’s work has been singled out by a number of industry groups and awards programs, including the American Photography annual and the International Motion Art Awards. In November, he spoke at the first-ever AI-AP Big Talk symposium in Los Angeles, where he told a group of filmmakers and photographers transitioning to motion how he comes up with ideas, and why ideas are so important.

“You remember imagery with a great idea behind it,” he said. “What commercial clients look for today, more than ever, is a photographer or director who comes with a vision and a strong concept.” One of the exercises he uses to produce ideas, he said, was to “consider things out of context.” A recent personal project called “The Peg” — a series of stills and a short motion piece featuring a wooden sculpture with movable parts — began, for instance, as an homage to large-format photography.

“In this world of digital effects, CGI and green screens, ideas with minimal tricks always stand out,” he said. “In motion work, you don’t need a big story to tell. You need simple concepts told well.”

Cutler’s work — and his affection for sketches — reflects his background as a one-time graphic-design student. He discovered that what he liked doing most was creating photographs, however, and apprenticed with a number of New York commercial photographers. They included David Langley, who’s bustling studio was one of the busiest in town. “He had a two-story facility you could drive a truck into,” Cutler recalls. “He had two set builders, a carpentry shop and two darkrooms. It was like a city. And he rented space to other photographers, so I got to work with people like Bert Stern and Dennis Manarchy.”

The biggest lesson he learned from Langley, he says, was that he didn’t need to specialize.

“Back at the time, everybody thought you had to do one thing — you’re a food photographer, or you’re a car photographer. But because of David I never paid attention to that. I have a very short attention span and like to do different things. It was going against the grain. But even today I highly recommend to students to not specialize. To me, whatever you’re doing is about your ideas.”

The Feasibility Factor

Cutler’s first big break was an assignment to shoot an ad campaign for Steuben Glass, and his career took off quickly from there.

“I never showed my conceptual side in the early years — it was all about shooting assignments,” says Cutler. “Now I’m doing what I love to do the most, working with agencies and clients directly, coming up with concepts and then shooting them.”

Cutler’s approach to ideas and how he presents them to clients has changed over time, because not all ideas, or sketches, are equal: Some are sketchier than others.

“What I’ve found is that I used to come up with a bunch of ideas that I’d sketch, and then I’d present them without really thinking whether they could feasibly be done,” he says. “I’d come up with an idea, and the client would say it was great, and then the idea would just die when we tried to make it. It got me into trouble all the time. So now, before I lay out all my sketches, I make sure that all of them — from my favorite to my least favorite — is something that I can make a great image out of. You have to be realistic. You can’t sketch something you can’t execute technically or financially.”

Peg from Craig Cutler on Vimeo.

The key is finding ideas that match feasibility with ambition. Recently Cutler shot a big-production TV spot for pulmonary cancer awareness by renting

out Chase Field, the home of Major League Baseball’s Arizona Diamondbacks, and shooting a faux ballgame in front of thousands of empty seats. He’s also working on a personal film

documentary project about a young boxer.

“It’s not usually how I work,” he says. “I usually have a very preconceived idea of the things I’m going to do, but this project is looser in a sense. It can’t be a standard documentary with interviews cut into the story.” Rather, the film focuses on what distinguishes all of Cutler’s work — beautifully shot details, with boxing as a visual metaphor for larger ideas about effort and redemption.

At the same time, he’s been shooting a new personal series: portraits of orange safety cones gathered from roadsides across America and shipped to his New York studio. “It’s intense and beautiful, a kind of pure photographic study,” Cutler says. And that’s a very big idea.