Photographer Profile - Kathy Shorr: "The project is meant to show the reality of what guns do to people"

|

|

|

And yet in a way she has — 101 times.

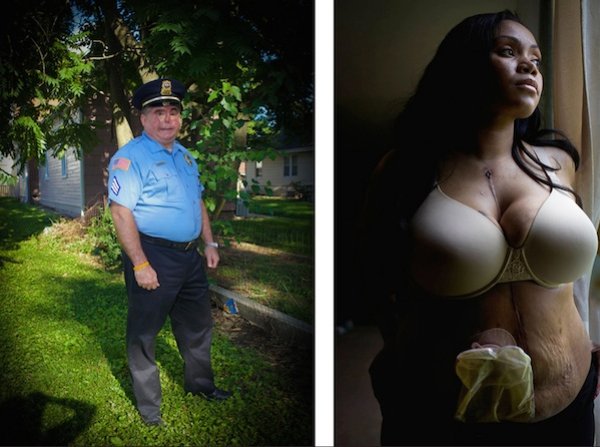

In 2013, Shorr began photographing survivors of gun violence at the very spots where the violence happened. She often asked her portrait subjects to reveal the scars they’d been left with. Her series, called simply “Shot,” has gotten considerable media attention over the past three years, and the stories about the work form a timeline of sorts that traces Shorr’s journey along a trail of suffering from one end of the United States to the other.

In 2014, for instance, when she was a year into the project, Shorr was interviewed by American Photo. At the time she had photographed 30 people, including a 77-year-old Marlys of Canoga Park, California, who had been shot by her abusive husband when she was 62.

In 2015, when Shorr was interviewed by Slate, she was up to 51 survivors. One of them was Jon, a police sergeant from Belleville, Illinois, who was shot in the face by a man who had just murdered two other people. There was also Moni, one of the people wounded by James Holmes in a mass shooting at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, in 2012.

In all, Shorr traveled some 100,000 miles across America to complete the project, which she did on December 17, 2015, when she photographed her 101st subject, Karissa of Sisseton, South Dakota, who was shot by an abusive boyfriend who’d gone on a killing spree that left three other people dead. “I’d given myself a deadline to finish by the end of that year,” Shorr recalls. “I’d become very determined to get it done because I told the people I had photographed that I was going to do a book. It was a kind of promise. They had been so giving with me, sharing their stories and letting me see parts of their bodies that no one else had seen. I didn’t want to let them down.”

The book, which Shorr funded with a Kickstarter campaign in 2016, has now been published. The people you meet in its pages, the 101 survivors, come from a wide variety of backgrounds and represent different races and ethnicities. They range from age eight to 80. Some were injured in high-profile shootings, like the one in Aurora, while others were shot by friends or lovers. Some were gun owners themselves, including an NRA member who says he is alive today because of the licensed weapon he owns.

“The project is meant to show the reality of what guns do to people — all different kinds of people,” Shorr says.

Deadly Husbands

The people Shorr photographed represent a catalog of the disorder, criminality, and fury set loose by guns in a country that is filled with them. But there is also randomness and a twisted sense of luck in their stories. The NRA member Shorr photographed, Jeff, was shot eight times — twice in the head — in his Memphis home. The person he’d testified against in a child-custody case had hired a someone to kill him. Droke fired back with his own gun as the shooter fled in his car. Another man in the book, Kenny of Rougemont, North Carolina, was shot 20 times by a mentally ill neighbor.

Demetria of Newport News, Virginia, was just sitting on her bed talking to her mother when a bullet came through a window and hit her. Katrina was left paralyzed by an errant bullet from a drive-by shooting in Aurora, Colorado.

“Many people were sitting in their cars when a stray bullet came along,” says Shorr.

One circumstance stands out, though: Shorr says that 20 percent of the survivors she photographed were victims of domestic violence. In her book, she notes that a joint study by Harvard and Duke universities found that an estimated nine percent of adult Americans with impulsive anger issues either own a gun or have access to one. As Nicholas Kristof of The New York Times noted in February, husbands are deadlier than terrorists in the U.S.

Shorr was teaching photography in a New York City public high school as a full-time teaching fellow when she began thinking about the project. “I noticed that kids would come in wearing memorial cards with the names of friends and relatives who had been killed by guns,” she says. “These dead people had a kind of folk-hero status, and I started to wonder about people who were shot and survived — who was thinking or talking about them?”

As she developed her ideas, she decided to frame the discussion of gun violence in a way that would be meaningful to as many people as possible.

“Nobody was talking about gun violence in a way that there was any gray area — everybody was entrenched in their position that either nobody should have guns or everybody should have as many guns as they want," Shorr says. "I thought if I could show people who were touched by gun violence — a broad range of survivors — then people would be able to look at the pictures and say, ‘Oh, that woman is like me,’ or ‘That man is like me.’ And if they couldn’t identify with a person, they might identify with the banal places the violence took place. If you can’t identify with the deputy sheriff in Texas whose husband shot her, you might be able to relate to the fact that she was shot in a Walmart parking lot, because you go to Walmart."

“It Was All So Real”

Shorr is a native New Yorker who studied photography at the School of Visual Arts and found early success with a fine-art project she shot while working as a limousine driver in Brooklyn. The work, character studies of her passengers, was exhibited at the Visa Pour l’Image photojournalism festival in France.

Later she dropped photography for several years. “I was frustrated because I was working on a project and I thought it needed sound, but I didn’t want to go back to school to learn video,” she says. Eventually she found her way back to her cameras. She’d been toying with the idea of a project about survivors of gun violence when she heard a story on local TV news about a shooting in Brooklyn in which a man was seriously injured. She went to her computer, found him and sent an email. His name was Antonius, and he became subject number one of “Shot.”

Antonius had been standing at a crowded Brooklyn street corner at 2:30 in the afternoon when a bullet struck him. “It was fired by a man who saw his girlfriend there and decided it was a good time to shoot her,” says Shorr. Eight weeks after the shooting Shorr returned to the corner with Antonius, who had prepared for the experience by taking a Xanax.

Finding the next 100 people for her project took “an incredible amount of research and computer time,” says Shorr. Because the work was self-financed, she tried to group subjects together — photographing several on a trip to Los Angeles, for instance, and several more on a swing through Utah, Wyoming and Montana. A typical portrait session might last two hours.

“I like to talk to people before I photograph them,” Shorr says. “You don’t want to just meet someone at the street corner where they were shot. We’d meet at a McDonald’s or Starbucks and have coffee and go off and do the photography. If they’d been shot in their own homes, then we would meet there.”

Most of the people she photographed found the experience cathartic, says Shorr. But the evidence of their trauma is there to see in her pictures. One man, Albert of St. Louis, who had been shot in the stomach with a shotgun after cashing his paycheck on a street known as “Dead Man’s Alley,” said going back to the location sent shivers down his spine.

“I looked brave,” he told Shorr later, “but, hey, it was all so real.”